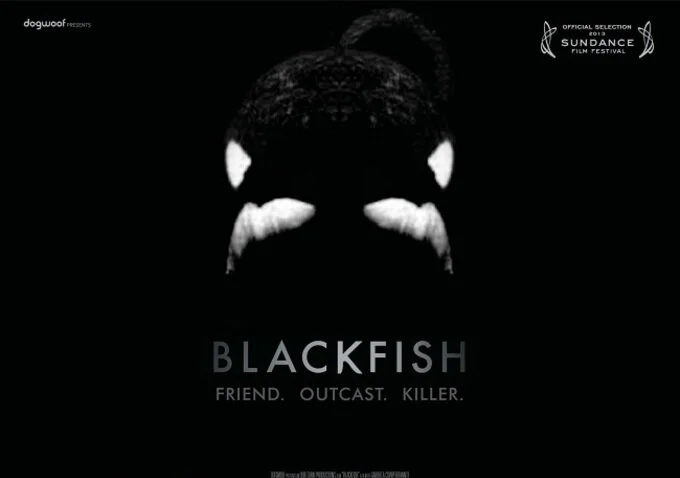

Blackfish

28 February 2014 ∙ Originally published in The Muse at Dreyfoos

Living in Florida, it’s easy to take all the attractions and tourist traps for granted as Floridian institutions and not think too much about what happens behind the scenes. Places like SeaWorld, an Orlando vacation staple since 1973, are known for providing tourists and residents with aquatic-themed fun and up-close interactions with orcas, including the world famous Shamu. Year after year, people from across the globe pour into a sweaty, moist stadium to obliviously watch trainers perform stunts with these gigantic animals without giving it a second thought. “Blackfish,” directed by Gabriela Cowperthwaite, seeks to inform the public as to what is happening behind closed tanks and expose the wrong-doings of the SeaWorld facilities.

First screened at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, “Blackfish” follows two tragically interrelated stories: the story of Tilikum, a 12,000-pound orca involved in the death of three people throughout his life in captivity, and a history of SeaWorld’s sometimes-fatal killer whale incidents.

Captured off the coast of Iceland in 1983 at the age of 2, Tilikum was first placed in captivity in Sealand of the Pacific, a small aquarium in Canada. The film claims Tilikum was bullied by the larger orcas, who were all forced to share a tiny, windowless capsule overnight, which psychologically scarred the whale. When a young trainer that fell into the orca tank in 1991 was dragged down and drowned by the orcas, fingers were pointed at Tilikum and he was transferred to SeaWorld Orlando. In 1999, a man evaded park security and managed to sneak into the the orca pool and was found dead, stripped and draped across Tilikum’s back.

Through interviews with past trainers and staff as well security footage, Cowperthwaite questions the validity of someone sneaking into such a highly guarded area and being mauled by a giant orca without anyone, including the park’s security, noticing anything. She also exposes several aspects of the whales’ captivity that SeaWorld vehemently opposes. Former trainers state that the whales are often denied proper medical care and attention. Another issue stems from the fact that orcas have a highly developed language that varies from pod to pod. This causes problems when SeaWorld management carelessly separates whales from their pod and the whales suffer the consequences of miscommunication-fueled violence.

Although Tilikum had already posed a threat to the safety status of SeaWorld, he was not the first orca to cause problems. One of Cowperthwaite’s main claims was that humans were not meant to interact so closely with wild animals, even in captivity. These animals, while usually docile and cooperative, often defy their trainers and sometimes injure them. Graphic footage of whales dragging, pinning, tossing around, roughing up and in one instance, jumping on top of a trainer, reveal that altercations between whales and humans have been happening since they were first put together.

The bulk of the film focuses on the 2010 death of experienced trainer Dawn Brancheau, who was dragged underwater and torn apart by Tilikum during one of the “Shamu” shows. While this incident set off a number of lawsuits against SeaWorld, Tilikum continues to perform in public shows with minimal new measures taken to ensure safety.

Keeping animals in captivity has always proved controversial. Many claim that companies exploit animals’ freedom in exchange for money and others see it as a harmless venture. The film does an incredible job of advocating its agenda; it presents fact after fact in a creative, well-paced way. Interviews with everyone from former and current orca trainers from around the world, marine biologists and former whalers make it apparent that close contact with these enormous creatures is not only dangerous to humans but destructive to the whales themselves.

Although it was released in cinemas in July, “Blackfish” was somewhat of a sleeper hit, not coming to the forefront of the public’s knowledge until the film’s availability on Netflix. The film gained serious press coverage in December, when several high-profile music acts such as the Beach Boys, Heart, Willie Nelson, Pat Benatar and the Barenaked Ladies canceled concerts at SeaWorld and its sister park, Busch Gardens.

“I don’t agree with the way they treat their animals,” Willie Nelson explained in an interview with CNN, “It wasn’t that hard [of] a deal for me.”

The highly anticipated upcoming Pixar film “Finding Dory” altered its ending after the producers saw the documentary.

In addition to refusing to participate in the film’s production, SeaWorld printed a full-page open letter in several magazines and set up a section on their website titled “Truth About Blackfish,” in hopes to correct what they think are inaccuracies in the film’s arguments. The documentary has now found itself in the middle of a media circus, with each side constantly attempting to have the final word on the issue. When several interviewees, as well as some of Brancheau’s family members, were quoted saying they did not approve of the final product’s agenda, Cowperthwaite invited SeaWorld representatives to a debate in a public forum, which SeaWorld promptly rejected.

It’s unfortunate that an accurate representation of the truth will be hard to come across, since the nature of the situation is not as black-and-white as the downtrodden victims caught in the middle of it.

“Ultimately,” Cowperthwaite said, “I think the trainers and the animals are safer as a result of this film. I can only hope [Brancheau] would be happy about that.”