Bonnets, Guns and Trails: Westerns Made by Women

25 June 2017 ∙ Originally published in Brattle Film Notes

The classic imagination of the Western is decidedly masculine, with an iconography pretty much dominated by the male presence. Yet, women directors made and are still making Westerns.

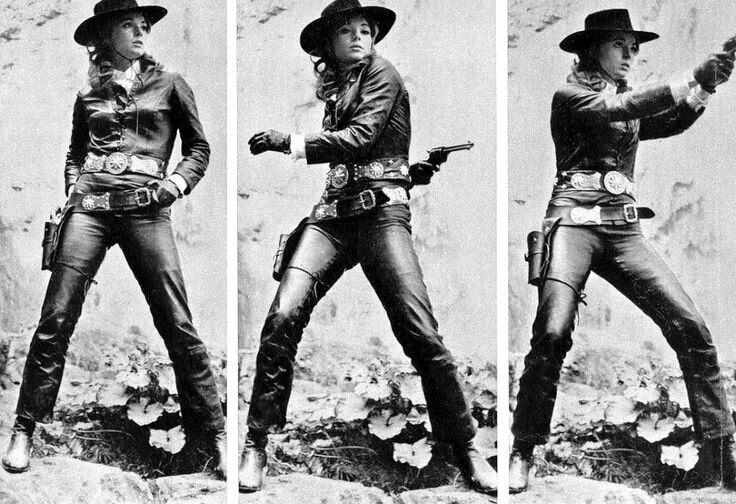

The Belle Starr Story (1968) dir. Lina Wertmüller

The only Spaghetti Western ever directed by a woman (who would later go on to become the first woman ever nominated for the Best Director Oscar), The Belle Starr Storyis a sordid revision of the life of the infamous outlaw. More preoccupied with her usual battles of the sexes and themes of memory and trauma than with historical accuracy, Wertmüller casts fashion model Elsa Martinelli as a glamorous sharpshooter with winged eyeliner and black leather suits.

The episodic plot sees the rough-playing Starr meeting her match in cocky outlaw Larry Blackie (George Eastman), who engages her in a fittingly perverse courtship that’s equal parts rolls in the hay and heated pistol duels. Through flashbacks, we learn how Starr’s troubled upbringing with a sadistic uncle and her affair with a dangerous outlaw led to her life outside the law with Jesse James’ notorious gang. A melodramatic exercise that pairs the most exploitative aspects of an overripe genre with Wertmüller’s signature wit, the film is a rare amalgamation of style, Italian sensibilities and late ‘60s trash.

Thousand Pieces of Gold (1991) dir. Nancy Kelly

Polly Bemis, a Chinese American pioneer and the subject of a little-known historical novel, is the hero of Nancy Kelly’s Thousand Pieces of Gold, which posits her self-esteem and enduring dignity as the virtues which helped Bemis successfully navigate a world determined to destroy her. Born in China as Lalu (Rosalind Chao), she is sold by her destitute family to a Chinese “wife trader” in Idaho, where she is renamed “China Polly” and expected to work in a brothel. Dead-set against giving up control over her life and body, Polly threatens the trader and convinces him to let her live as a saloon maid to pay off her purchase, eventually falling in love with his partner, Charlie Bemis (Chris Cooper). This being the racially fraught time before the Chinese Exclusion Act, the couple is eventually run out of town and forced to find happiness elsewhere.

Kelly – a North Adams, Mass. native – does not shy away from depicting the cruelty, racism and sexism faced by Polly, who led a comparatively smoother life than many other Chinese American women at the time. Bolstered by an inspiring performance from Chao, this Western romance might be more character drama than shoot-em-up bonanza, but remains faithful to the genre’s love for gutsy outsiders who dare to live by their own rules against all odds.

The Ballad of Little Jo (1993) dir. Maggie Greenwald

Based on true accounts of the life of Josephine Monaghan, The Ballad of Little Jo is an interesting look at a quietly remarkable existence. Ousted from her Boston society family after birthing a child out of wedlock, a young woman decides to try her luck in the rustic expanses of 1800s Idaho. Quickly disillusioned and angered by the two choices of livelihood given to most women in the West – either prostitute or homemaker – she scars her face, changes her wardrobe and rides into Ruby City as Jo.

Though not much is known about the historical figure, whose secret was taken to her grave and only discovered by an undertaker, Greenwald mines the story for rich explorations of the role-playing inherent in our lives. Jo (Suzy Amis), through hard ranch work and detached stoicism, comes to be accepted as a member of the town and it’s blatantly sexist male circles. But when Jo hires Tinman, a Chinese laborer, to work on the ranch, identity and performance are questioned as the two discover the cost of each other’s successes in a restrictive society.

Greenwald never directed another proper Western, but has shown her interests to lie in the ways women and minorities navigate hostile surroundings. Her film Songcatcher (2000) traces one woman’s career as a musicologist in North Carolina as she faces professional hardships and sexual discoveries. Her most recent film, Sophie and the Rising Sun (2016), follows the romance of an interracial Southern couple on the eve of the Pearl Harbor attacks.

Ravenous (1999) dir. Antonia Bird

Arguably the first and only vampire cannibal Western-comedy in existence, Ravenous would surely sink under its preposterous ambitions were it not as indelibly fun. When Second Lieutenant Boyd (Guy Pearce) discovers that other soldiers’ blood dripping into his mouth gave him superhuman strength during a bloody episode of the Mexican-American War, he is banished to a remote outpost in the Sierra Nevadas. There, he meets F.W. Colqhoun (Robert Carlyle), who tells him of a wagon expedition gone cannibalistic and hints at the Algonquian folklore that those who eat the flesh of another being inherit their strength but become cursedly insatiable. Horror and comedy – often alternately, often together – inevitably ensue.

Beset with production difficulties from the start, when original director Milcho Manchevski became frustrated with studio meddling and would-be replacement Raja Gosnell was scorned by the cast, Antonia Bird stepped in at the recommendation of Carlyle, who had collaborated with her before. In a virtuoso move, Bird capitalized on the trainwreck that the production had become and shot the film through a black comedy lens, satirizing Manifest Destiny and the ideals on which the West was founded to create an unforgettable cult classic.

The Outsider (2002) dir. Randa Haines

Set in an Amish-like enclave of rural Montana, The Outsider sees wounded gunslinger Johnny (Tim Daly) take refuge in a young widow’s farm. Rebecca (Naomi Watts), the young sheep farmer and single mother who takes him in, never questions his predicament and promises to nurse him back to health despite the protests from her conservative community. While the two inevitably fall in love and are shunned by the community, the cold-hearted cattle baron (Keith Carradine) who murdered Rebecca’s husband still smarts over a land dispute and plans his revenge on the town.

Haines, best known for directing the film adaptation of Children of a Lesser God (1986), creates a strong sense of natural atmosphere, lingering on shots of the pastoral terrain and drenching the movie in blues and yellows. Similar in plot to the John Wayne vehicle Angel and the Badman (1947), the film makes the most of its stars’ abilities, with much emphasis placed on Rebecca’s inner turmoil as she struggles to connect her desire to help the stranger with her communal values.

Meek’s Cutoff (2010) dir. Kelly Reichardt

Though the courage and resilience of Westward-bound pioneers has been the overarching theme of many a Western, Meek’s Cutoff is one of the few to question their blind audacity. Kelly Reichardt brings her slow-burning pensiveness to this meditation on Manifest Destiny and the people who boarded covered wagons with virtually zero knowledge of the road ahead. Frequent collaborator Michelle Williams stars as a quiet woman who begins to question the ability and know-how of their caravan leader, real-life trail guide Stephen Meek, once the journey stretches far past it’s two-week timeline. With anxiety and doubt settling in, the women in the group find themselves frustratingly at odds with the men’s poor decisions.

Shot on the historic Oregon Trail, whose intimidating vastness only makes the travelers’ cluelessness all the more apparent, the film brings a unique perspective to a topic seldom considered from a woman’s point of view. That these women had no choice but to sit back and watch as their husbands carved out the futures of their families – and of the country – is a quiet tragedy in itself, one which Reichardt explores with her contemplative camera. Strong women of the West have long been of interest to the writer-director, who tread similar ground in Wendy and Lucy (2008) and Certain Women (2016), both released to critical acclaim.